MENSTRUAL CYCLE

A woman's reproductive system is regulated by the hormonal interaction between the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland and ovaries. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), a small peptide, is secreted by the hypothalamus and triggers the release of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary gland.1

LH and FSH promote ovulation and stimulate the secretion of oestrogen and progesterone from the ovaries. Oestrogen and progesterone circulate in the bloodstream and act on organs such as the uterus, vagina and breasts, as well as bone, skin and muscle.1

FSH stimulates follicle growth in the ovaries culminating in a follicle that releases an oocyte at ovulation and then forms a corpus luteum. If no pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum breaks down and levels of oestrogen and progesterone decline, leading to the periodic discharge of blood and sloughed endometrium. This occurs during each cycle in the absence of pregnancy.1

However, if implantation occurs, the corpus luteum does not degenerate and continues to produce large amounts of oestrogen and progesterone in early pregnancy, supported by human chorionic gonadotropin produced by the developing embryo. At around 10 weeks of gestation, the placenta produces large amounts of oestrogen and progesterone and the corpus luteum decreases in size.1,2

Oral contraceptives mimic ovarian hormones by inhibiting the release of GnRH and thereby inhibiting the release of the pituitary hormones that stimulate ovulation. Oral contraceptives also affect the uterus lining and cause the cervical mucus to thicken, preventing sperm from entering the cervix and making implantation difficult.3

USE OF CONTRACEPTION

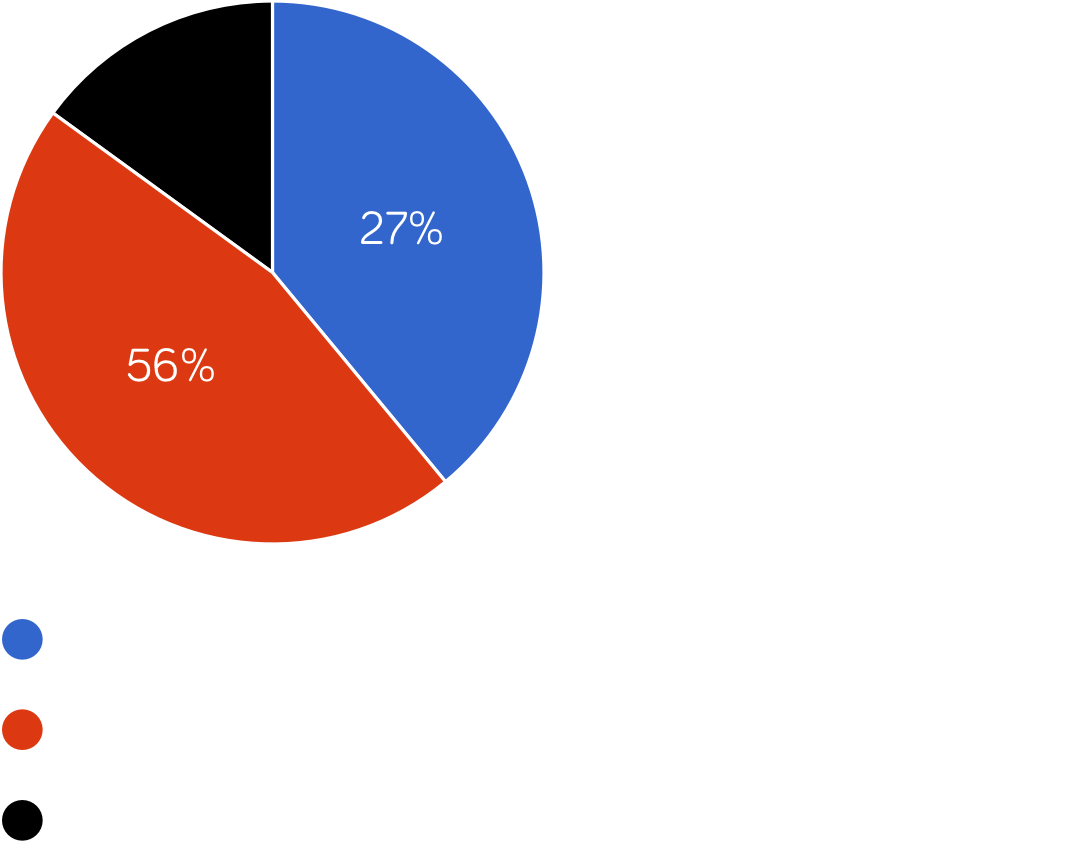

National data for England indicates that 56% of women were using long acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in 2021/22, an increase of 10% points from 46% in 2020/21. There was a sharp decrease in women using contraceptive pills as their main method of contraception and a rise in the use of intrauterine systems (IUSs), intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants.4

Use of oral contraceptives decreased from 39% in 2020/21 to 27% in 2021/22; however, these remain the most commonly used method of contraception overall, and were the most commonly used method in all age groups, with the exception of those aged 35 years and over, for whom IUSs were most popular.4

TEMPERATURE-BASED CONTRACEPTION

Some women choose to use the temperature method as a form of contraception. Using an ear or forehead thermometer would not be accurate for this so either a digital thermometer or a thermometer specifically designed for natural family planning should be used.

This method is done by the woman measuring her body temperature every morning before getting out of bed, ideally at the same time every morning. The temperature should be taken before eating or drinking. A small rise in temperature, usually around 0.2C, occurs after ovulation. Women should therefore look out for 3 days in a row when their temperature is higher than all of the previous 6 days. It is likely they are no longer fertile at this time. The reliability of the temperature method can be improved by combining it with monitoring of menstral cycle length and changes in cervical mucus.5

CONTRACEPTION CONSIDERATIONS6

If a woman requests contraception, then her needs and personal circumstances should be considered and discussed. Pregnancy should be excluded, and the healthcare professional should be reasonably certain that the woman is not currently pregnant. However, if the woman is likely to be at continued risk of pregnancy or has expressed a wish to begin contraception as soon as possible, one of the following methods can be prescribed until a pregnancy test can be taken:

● Combined hormonal contraception

● Progestogen-only pill (POP)

● Progestogen-only implant

● Progestogen-only injection.

A full medical history and a clinical examination should be performed to identify any factors that can affect the choice of contraception for example, hypertension, migraines, allergies, lifestyle factors (such as smoking), reproductive history, medications and age.

When a woman is considering contraception, her preferred method, future plans for having children, personal views and beliefs about contraception, and family and partner attitudes towards contraception should be discussed.

The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraception (UKMEC) provides guidance to support prescribing of combined hormonal contraception, progestogen-only contraception and intrauterine contraception, to ensure that these methods can be safely used.

UKMEC considers a woman’s personal characteristics, reproductive history, age, parity, smoking, obesity and cardiovascular risk factors by assigning a category from 1 to 4 for each method of contraception, with UKMEC 1 being no restriction for use of the method and UKMEC 4 being an unacceptable health risk for that method.

The UKMEC states that women should be given accurate information on methods for which they are medically eligible and that would best suit their needs. Healthcare professionals should give information on efficacy, risks and side-effects, advantages and disadvantages, and non-contraceptive benefits of all methods available.

CONTRACEPTION FOR WOMEN OVER 40

Once women reach 40 years old they experience a natural decline in fertility but still require contraception until they reach menopause to avoid an unplanned pregnancy. Women entering perimenopause (see below) may experience symptoms relating to fluctuating hormone levels and it is important to consider that their background risk is different to that of younger women. Perimenopausal women are at an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), cardiovascular disease, breast cancer and other gynaecological cancers, and this risk affects the type of contraception they can use.7

Healthcare professionals should discuss the effectiveness, risks and benefits and side-effects of all available methods of contraception; however, LARCs are considered to be most effective in this patient group. The use of any contraceptive should not affect the timing and duration of menopause but could mask symptoms that indicate perimenopause or the start of menopause and therefore, some women may hesitate to use contraception. Healthcare professionals can refer to the UKMEC to assess a woman’s eligibility for contraceptive methods before they prescribe.7

At the age of 50 years old, women should be encouraged to return to discuss contraception or if they experience any significant changes in their health. In general, all women can cease contraception after the age of 55 years as spontaneous conception after this age is exceptionally rare.8

MENOPAUSE

Menopause occurs when menstruation ceases due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity. The average age of menopause in the UK is 51 years but this can vary widely.

One in 100 women experience premature ovarian insufficiency (POI)—menopause occurring before the age of 40 years old, which can occur naturally or as a result of medical or surgical treatment.9,10

DIAGNOSIS OF MENOPAUSE

Perimenopause is the period before menopause when the endocrinological, biological and clinical features of approaching menopause start and is also known as the menopausal transition or climacteric. If a woman is over the age of 45 years old and has vasomotor symptoms and irregular periods, then this is adequate information to diagnose perimenopause.11

Postmenopause is the time after a woman has not had her period for 12 consecutive months.11

Menopause is associate with high FSH and LH levels and low oestrogen levels, which causes irregular periods and also affects the body more widely, impacting on quality of life. Common symptoms include hot flushes, night sweats, insomnia, joint pains, irritability, low mood, loss of libido, vaginal dryness and/or memory problems.11

Eight out of 10 women experience some of these common symptoms, which typically last for 4 years after their last period and can continue for up to 12 years in 10% of women. Prolonged absence of oestrogen also increases the risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular problems.9 Oestrogen can be taken in the form of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to help reduce menopausal symptoms.10

The levels of serum FSH should not be used to diagnose perimenopause or menopause in otherwise healthy women over the age of 45 years with typical symptoms, who are not using hormonal contraception. Serum FSH testing can be considered in women over the age of 45 years presenting with atypical symptoms, those aged 40–45 years old presenting with symptoms, and those younger than 40 years old with suspected POI.10

MANAGING MENOPAUSAL SYMPTOMS12

A woman presenting with symptoms of menopause should be assessed by asking about her symptoms and quality of life, lifestyle, contraception, smear status, family history, previous treatments and wishes, current medication, and comorbid conditions.10

A holistic and individualised approach should be used to help each woman manage her symptoms. This should include recommending sources of information and support, and lifestyle measures for symptom relief, such as exercise, dietary modification (including ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake), smoking cessation and avoiding excessive alcohol. Bone health and contraception should also be regularly reviewed. The British Menopause Society, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Society for Endocrinology have produced a joint position statement to provide guidance to healthcare practitioners who offer care to women experiencing menopause.13

If a woman requests HRT to help manage her menopausal symptoms, the healthcare professional should discuss with her the choice of preparations, including benefits and risks, adverse effects, and contraindications.10

USE OF HRT

Approximately a million women in the UK use HRT to help manage their menopausal symptoms.9 In England and Wales £57.2 million is spent annually on HRT and topical oestrogen.11

HRT prescribing has increased dramatically in the past year. There were 7.80 million items prescribed for HRT in England in 2021/22, a 35% increase from 2020/21. An estimated 1.93 million identified patients were prescribed HRT in England in 2021/22, an increase of 30.5% from an estimated 1.48 million patients in 2020/21.14

The lowest number of estimated identified patients who were prescribed HRT in 2021/22 was found in areas of greater deprivation, with almost twice as many patients receiving prescriptions in the least deprived areas compared with the most deprived. A greater proportion of patients from the most deprived areas were under the age of 60 years old.14

Since April 2023, women experiencing menopause symptoms can purchase a new HRT prescription payment certificate, which provides a year’s worth of menopause prescription items for the cost of two single prescription charges.15

TYPES OF HRT

The appropriate type of HRT for an individual woman depends on several factors, including her symptoms, stage of the menopausal process, and whether or not she has had a hysterectomy.9 Systemic treatments are available as oral tablets, patches and gels (transdermal); local preparations are available as creams, tablets, pessaries and a vaginal ring. One brand of vaginal oestradiol tablets can be purchased from a pharmacy without a prescription.

There are two main types of HRT; combined HRT (oestrogen and progestogen), which is suitable for women who still have their uterus, and oestrogen-only HRT, which is suitable for women who have had their uterus removed.16

Combined HRT17

Oestrogen helps relieve menopausal symptoms and progestogen is added to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. This type of HRT is also known as cyclical or sequential HRT, or continuous combined HRT and can be taken monthly or 3-monthly. For monthly HRT, oestrogen is taken every day and progestogen is taken alongside it for the last 14 days of the woman’s menstrual cycle. The 3-month regimen consists of taking oestrogen every day with the progestogen taken for approximately 14 days every 3 months. The oestrogens used in HRT are generally ‘natural’ hormones found in normal physiology,10 but a combined contraceptive was recently launched containing the synthetic oestrogen estetrol. Conversely, progestogens in HRT are usually synthetic,10 although there is now a continuous combined ‘bioidentical’ capsule containing estradiol and progesterone.

Oestrogen-only HRT17

This type of HRT is usually taken every day without a break.

SHORT-TERM SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

For most healthy women, particularly those under the age of 60 years, the benefits of short-term HRT outweigh the risks.10,11 When HRT is used, the lowest dose should be used for the shortest possible time.10

For vasomotor symptoms:9

● Offer HRT.

For psychological symptoms:9

● Consider HRT to alleviate low mood.

● Consider cognitive behavioural therapy to alleviate low mood or anxiety.

For low sexual desire:9

● Consider testosterone supplementation if HRT alone is not effective.

For genito-urinary syndrome of menopause:9

● Offer vaginal oestrogen (including to women on systemic HRT) and continue treatment for as long as needed to relieve symptoms; if not effective, consider increasing dose with specialist advice.

● If systemic HRT is contraindicated, consider vaginal oestrogen after seeking specialist advice.

● Explain to women that:

— Symptoms often come back when treatment is stopped.

— Adverse effects from vaginal oestrogen are very rare.

— They should report unscheduled vaginal bleeding.

● Advise women with vaginal dryness that moisturisers and lubricants can be used alone or with vaginal oestrogen.

● Do not offer routine monitoring of endometrial thickness during treatment for urogenital atrophy.

Women who are unable to take HRT can be offered antidepressants, cognitive behavioural therapy and/or clonidine, gabapentin and vaginal moisturisers/lubricants for vasomotor symptoms, depression or anxiety, and urogenital symptoms, respectively. They should also have regular reviews to assess the efficacy and tolerability of these treatments. If required, a referral to a specialist can be made too.10

BENEFITS AND RISKS OF HRT

A Cochrane review suggested that taking HRT before 60 years of age, or within 10 years of menopause starting, could reduce atherosclerosis progression, coronary heart disease and death from cardiovascular causes, as well as all-cause mortality.12

The risk of VTE is increased by taking HRT compared with baseline population risk and the risk of VTE associated with HRT is greater for oral than transdermal preparations. The risk associated with transdermal HRT at a standard therapeutic dose is no greater than the baseline population risk. For women with a BMI over 30kg/m2 and an increased risk of VTE, transdermal HRT should be considered in preference to an oral preparation. Women at high risk of VTE (due to family history of VTE or hereditary thrombophilia) should be referred to a haematologist before considering HRT.18

Healthcare professionals should reassure women going through menopause that taking HRT does not increase cardiovascular risk when started under the age of 60 years old. Taking oestrogen-only HRT is associated with no or reduced risk of coronary heart disease, and combined HRT is associated with little or no increased risk in coronary heart disease. Women taking oral (but not transdermal) HRT have a small increase in the risk of stroke but the risk of stroke for women under the age of 60 years is very low.18

There is no increased risk of type II diabetes when taking HRT (either oral or transdermal) and HRT is not associated with an adverse effect on blood glucose control. Women with type II diabetes can be considered for HRT after taking specialist advice.18

The risk of breast cancer associated with HRT varies from one woman to another, according to underlying risk factors. Oestrogen-only HRT is associated with little or no change in the risk of breast cancer. Combined HRT can be associated with an increase in the risk of breast cancer. This is related to treatment duration and reduces after stopping HRT.18

The risk of fragility fracture for women going through menopause is low but can vary from one woman to another. The risk is lessened by taking HRT but this benefit is only maintained during treatment. It may continue for longer in women who take HRT for longer.18

There is limited evidence to suggest that taking HRT can improve muscle mass and strength, and its effect on the risk of dementia is unknown.9

REVIEW AND REFERRAL

The risks and benefits of taking HRT vary over time, and should be re-evaluated annually.12 There should not be any arbitrary limits placed on the duration of using HRT and if symptoms persist, then the benefits of HRT generally outweigh the risks.11 If the woman wishes to discontinue HRT, she should be advised what to expect once treatment is stopped.12

Women with POI and early menopause are encouraged to use HRT at least until the age of menopause. The combined contraceptive pill and HRT are both suitable options for hormone replacement in women with POI. However, HRT may have greater benefits for bone density and cardiovascular markers than the combined contraceptive pill.12

REFERENCES

1. McLaughlin J. Female reproductive endocrinology. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

2. Artal-Mittelmark R. Physiology of pregnancy. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

3. Casey FE. Oral contraceptives. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

4. NHS Digital. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services, England (Contraception) 2021/22. Methods of contraception. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

5. NHS. Natural family planning (fertility awareness). Last accessed April 2023.

6. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. Last updated September 2019. Last accessed April 2023.

7. FSRH. FSRH Guideline. Contraception for women aged over 40 years. Last updated September 2019. Last accessed April 2023.

8. FSRH. Claire Nicol. Half Day Hot Topic: Managing Women's Hormone Health 29 September 2021, Contraception for Women Aged Over 40 Years. Last accessed April 2023.

9. NICE. Menopause: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (NG23). 2015. Last accessed April 2023.

10. NICE. CKS. Menopause. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

11. PrescQIPP Community Interest Company. Menopause. B182. Last updated 2017. Last accessed April 2023.

14. NHS Business Services Authority. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT). England April 2015 to June 2022. Last updated October 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

15. GOV.UK. Press release. Hundreds of thousands of women experiencing menopause symptom to get cheaper HRT. Last accessed April 2023.

16. NHS inform. Hormone replacement therapy. Last accessed April 2023.

17. NHS. Types. Hormone replacement therapy. Last accessed April 2023.

18. NICE. NCC-WCH. Menopause. Full guidance. Clinical guideline. Last updated November 2015. Last accessed April 2023.

Published by Haymarket Media Group Ltd, Bridge House, 69 London Road, Twickenham, TW1 3SP

You acknowledge that whilst Haymarket endeavours to ensure that information on this site is accurate and complete at the time of first publication, it is provided only for general information, is not intended to address your particular requirements and does not constitute any form of advice or recommendation by Haymarket. You acknowledge that the information on this site does not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Haymarket, that such information should not be relied upon by you in making (or refraining from making) any specific investment or other business, professional or personal decisions and that you should seek independent professional advice before making any such decision. You also acknowledge that views and opinions expressed in content submitted by third party contributors are views and opinions of the authors of that content and not Haymarket’s views and opinions.

©2023 Haymarket Media Group Ltd.

Haymarket is certified by BSI to environmental standard ISO14001 and energy management standard ISO50001

REFERENCES

1. McLaughlin J. Female reproductive endocrinology. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

2. Artal-Mittelmark R. Physiology of pregnancy. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

3. Casey FE. Oral contraceptives. MSD Manual Professional Version. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

4. NHS Digital. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services, England (Contraception) 2021/22. Methods of contraception. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

5. NHS. Natural family planning (fertility awareness). Last accessed April 2023.

6. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. Last updated September 2019. Last accessed April 2023.

7. FSRH. FSRH Guideline. Contraception for women aged over 40 years. Last updated September 2019. Last accessed April 2023.

8. FSRH. Claire Nicol. Half Day Hot Topic: Managing Women's Hormone Health 29 September 2021, Contraception for Women Aged Over 40 Years. Last accessed April 2023.

9. NICE. Menopause: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (NG23). 2015. Last accessed April 2023.

10. NICE. CKS. Menopause. Last updated September 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

11. PrescQIPP Community Interest Company. Menopause. B182. Last updated 2017. Last accessed April 2023.

14. NHS Business Services Authority. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT). England April 2015 to June 2022. Last updated October 2022. Last accessed April 2023.

15. GOV.UK. Press release. Hundreds of thousands of women experiencing menopause symptom to get cheaper HRT. Last accessed April 2023.

16. NHS inform. Hormone replacement therapy. Last accessed April 2023.

17. NHS. Types. Hormone replacement therapy. Last accessed April 2023.

18. NICE. NCC-WCH. Menopause. Full guidance. Clinical guideline. Last updated November 2015. Last accessed April 2023.

Published by Haymarket Media Group Ltd, Bridge House, 69 London Road, Twickenham, TW1 3SP

You acknowledge that whilst Haymarket endeavours to ensure that information on this site is accurate and complete at the time of first publication, it is provided only for general information, is not intended to address your particular requirements and does not constitute any form of advice or recommendation by Haymarket. You acknowledge that the information on this site does not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Haymarket, that such information should not be relied upon by you in making (or refraining from making) any specific investment or other business, professional or personal decisions and that you should seek independent professional advice before making any such decision. You also acknowledge that views and opinions expressed in content submitted by third party contributors are views and opinions of the authors of that content and not Haymarket’s views and opinions.

©2023 Haymarket Media Group Ltd.